Evangelio de JuanDe Wikipedia, la enciclopedia libre El Evangelio según Juan es un libro de la Biblia en el Nuevo Testamento que contiene la historia de la vida de Jesucristo. La tradición atribuye la autoría de este evangelio al apóstol Juan el evangelista, aunque dada la fecha supuesta de redacción parece que no es así. Lo más probable es que fuera fruto de la comunidad fundada alrededor de uno de los discípulos de Jesús, llamado en el evangelio el discípulo a quien Jesús amaba, seguramente la de Éfeso.

[editar] EstructuraDespués de la introducción (1:1-5), de carácter puramente teológico, la narración del libro empieza en el verso 6, y consta de dos partes. La primera parte (1:6-capítulo 12) contiene la historia del ministerio público de Jesús desde su introducción por Juan el Bautista hasta su entrada en Jerusalén. La segunda parte (capítulos 13-21) presenta a Jesús con sus enseñanzas y ministerio a sus discípulos durante la fiesta de la Pésaj (13-17), y da cuenta de sus sufrimientos en la Pasión (18-19) y la aparición a sus discípulos después de su resurrección (20-21).Los puntos notables de este evangelio son (1) la relación entre el Hijo y el Padre, (2) entre el redentor y los creyentes, (3) el anuncio del Espíritu Santo como Consolador, y (4) el énfasis sobre el amor como un elemento de carácter cristiano. Se trata, probablemente, del evangelio más filosófico de todos los llamados canónicos. Este libro está escrito primariamente a los cristianos. Se supone que fue escrito en Éfeso, que después de la destrucción de Jerusalén (70 d. C.), vino a ser el lugar principal de vida cristiana. El evangelio fue escrito para personas conocedoras de la cultura judía y al mismo tiempo en contacto con el pensamiento griego; además se les pone en guardia frente al gnosticismo. [editar] DataciónLa datación mayoritaria sitúa a este evangelio en los años 90 d.C.Las dataciones más tardías están limitadas por el Papiro P52 (hacia 125-150) y por las menciones al evangelio de Juan que hacen Ireneo de Lyon y el Fragmento muratoriano hacia el año 180, así como Clemente Jaques y Tertuliano hacia 200. Las dataciones más tempranas (P. Mr and Mrs Smith; A. T. Olmstead; E. R. Goodenough; H. E. Edwards; B. P. W. Starther Hunt; K. A. Eckhardt; R. M. Grant; G. A. Turner; J. Mantey; W. Gericke; E. K. Lee; L. Morris; S. Temple; J. A. T. Robinson) se basan en los siguientes argumentos:

[editar] Véase también[editar] Enlaces externos

Gospel of JohnFrom Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia For other uses, see Gospel of John (disambiguation). The Gospel According to John (Greek: κατὰ Ἰωάννην εὐαγγέλιον, kata Iōannēn euangelion, or τὸ εὐαγγέλιον κατὰ Ἰωάννην, to euangelion kata Iōannēn), commonly referred to as the Gospel of John or simply John, is an account of the three-year public ministry of Jesus of Nazareth. It details the three-year public ministry from the witness and affirmation of Jesus by John the Baptist to his death, burial, Resurrection, and some post-Resurrection appearances. In the standard order of the canonical gospels, it appears fourth, after the synoptic gospels Matthew, Mark and Luke. The Gospel's authorship is anonymous. However, in chapter 21 it is stated that it derives from the testimony of the 'Disciple whom Jesus loved', identified by Early Church tradition with John the Apostle, one of Jesus' Twelve Apostles. The issue of authorship is quite controversial (see the discussion below). The gospel is closely related in style and content to the three surviving Epistles of John such that commentators treat the four books together.[1] Scholarly opinion is divided as to whether these epistles are the work of the evangelist himself or of his followers writing in his name. The epistles are addressed to a particular but unnamed church community, and the Gospel, too, may be addressed to the specific circumstances of that community. The evangelist urges his church to beware of internal factions and to reject false teaching. He seeks to strengthen the church community's resolution in the face of hostility and persecution from the Jewish leadership of the synagogue. It is now widely accepted that the discourses are concerned with the actual issues of the church and synagogue debate at the time when the Gospel was written[2] c. AD 90. It is notable that, in the gospel, the community still appears to define itself primarily against Judaism, rather than as part of a wider Christian church. Lindars 1990 points out that Christianity started as a movement within Judaism, but he says that gradually Christians and Jews became bitterly opposed to one another.[3] Of the four canonical gospels, John presents the highest Christology. It describes Jesus as the incarnation of the divine Logos, through which all things were made, and declares him to be God.[4] Only in the Gospel of John does Jesus talk at length about himself and his divine role, including a substantial amount of material Jesus shared with the disciples only. Here Jesus' public ministry consists largely of miracles not found in the synoptics, including raising Lazarus from the dead. Contrary to the synoptics, Jesus' miracles in John are signs meant to engender faith. In John, Jesus is the object of veneration.[5] Certain elements of the synoptics such as parables and exorcisms are not found in John. John presents a realized eschatology in which salvation is already present for the believer, and the verses that refer to the future coming of Christ were plausibly added later.[6] The gospel includes gnostic elements[7][8] and teaches that salvation can only be achieved through revealed wisdom, specifically belief in (literally belief into) Jesus.[9]

CompositionAuthorshipMain article: Authorship of the Johannine works

Traditional view

As the gospel's name implies, the author has traditionally been understood to be the Apostle John. This understanding of the authorship of the Fourth Gospel remained in place until the end of the 18th century.[10] John A.T. Robinson says that the Johannine tradition did not suddenly emerge around 100, but that there is "a real continuity, not merely in the memory of one old man, but in the life of an ongoing community, with the earliest days of Christianity."[11] According to the Church Fathers, John the Apostle was the last of the Evangelists to compose a gospel. The Bishops of Asia requested he write such a gospel in response to Cerinthus, the Ebionites and other Hebrew groups which they deemed heretical.[12][13][14] The second reason given for this work was that the Gospels of Matthew, Mark, and Luke only gave a history for the one year, of and following the imprisonment of John the Baptist. Therefore, the Evangelist expanded on the Synoptic gospels of which he had read and approved.[15][16] Johannine authorship was also evidenced by Polycarp, (who is said to have known the apostles), Irenaeus and Eusebius.[17][18] [19][20] Internal evidence that the author was the Apostle JohnSome scholars[who?] have interpreted certain passages as the author claiming to be an eyewitness.[21] Robert Kysar states only that the scene is related on the sound basis of eyewitness and that the appendix claim should not be assumed to have come from the same hand.[22] The text implies that the unnamed author is an apostle. 21:20–25 contain information that could be construed as autobiographical. Some believe that the first person "I" in verse 25, the disciple in verse 24 and the disciple whom Jesus loved (also known as the Beloved Disciple) in verse 20 are the same person.[23] Critics point out that the abrupt shift from third person to first person in vss. 24–25 indicates that the writers of the epilogue, (who are supposedly third-party editors) claim the preceding narrative is based on the Beloved Disciple's testimony.[24][25] In the synoptics, John is close to Peter, the chief apostle, in a way that, in John, the beloved disciple is close to Peter.[26] The consistent omission of John has traditionally been taken as evidence that John authored the Gospel.[26] External evidence that the author was the Apostle JohnBefore the end of the 2nd century, the Church had identified the author, the "disciple Jesus loved," as the Apostle John.[8] The writings of Papias, Justin, Dionysius of Alexandria, Origen, Eusebius, Irenæus of Lyons and Jerome provide a sound historical basis for this assertion.[10][17][27] Furthermore, scholars are unaware of any cogent historical document from the first three centuries that seriously challenges the authenticity of John.[21] John the EvangelistMain article: John the Evangelist  Russian Orthodox icon of the Apostle and Evangelist John the Theologian, 18th century (Iconostasis of Transfiguration Church, Kizhi Monastery, Karelia, Russia). The traditional view is that the Apostle John was an historical figure who, along with James and Peter, was one of the "pillars" of the Jerusalem church, as reported by Paul.[28] In the synoptics, he was one of the inner circle of disciples.[8][28] CerinthusThe Alogi, a 2nd-century sect that denied the doctrine of the Logos, ascribed this gospel, as well as the Book of Revelation, to the Gnostic Cerinthus.[29] Irenaeus, on the other hand, asserted that John wrote his gospel to refute Cerinthus.[30] Modern critical scholarshipTheissen and Merz regard the Gospel of John as more theological and less historical than the synoptics, and they dispute that the Apostle John was the author.[7] John's picture of Jesus is very different from the accounts in the synoptics.[31] In discussing these differences, scholars distinguish anecdotes from discourses. Anecdotes about Jesus' ministry in John are similar in style to those found in the synoptics, and often cover recognisably the same events. In several such instances John appears to draw on distinct source material, which often appears to be historically more reliable.[32] However, this anecdotal material also appears to have been extensively reworked, especially in order to dramatise the narrative.[33] The discourses in John are considered by Lindars to originate in homilies and sermons, that are predominantly the evangelist's own composition but which expound on a saying or action of Jesus from the tradition.[34] There is no consensus in current scholarship as to how far the material in John may derive from a historical 'Disciple whom Jesus loved',[35] but it is broadly agreed that the authorship of the Gospel should be credited to the person who composed the finished text, rather than to the source of material in the text;[36] and that this composition is to be dated around 85-90 AD,[37] a decade or more later than the most likely dates for composition of the synoptics. On account of this later dating, and also of the greater degree of editorial reworking detected in John, the Synoptic accounts are considered by Lindars to be more historically reliable.[35] J.A.T. Robinson, F. F. Bruce, and Leon Morris say that the gospel is equally theological and historical as the synoptics, and that it was written by the apostle.[38][39][40][41][42][43][44][45][46][47][48][49][50][51] Bart Ehrman hypothesizes that John was an illiterate, precluding him from authorship of the gospel attributed to him.[52][53] In his view, the Gospel of John is an account composed by an unknown writer who may have never met Jesus.[54] Geza Vermes sees the Fourth Gospel as being so hostile towards Judaism that the author might not even have been Jewish,[55][dubious ] thinking the claim of John's authorship to be falsified and not backed by any solid historical evidence.[55][dubious ] Since the author was fluent in Hellenistic philosophy, he says it could hardly have been John, described in Acts as "unschooled and ordinary."[Ac. 4:13][55][dubious ] Furthermore, Jesus was recorded as foretelling that John would suffer martyrdom along with his brother, James.[Mk. 10:39] [Ac. 12:2] [8][26] In addition, 5th and 9th century writers referred to an alleged passage by Papias indicating that James and John had been killed by the Jews, and their deaths are recorded in several early martyrologies; this evidence for John's martyrdom, however, is inconclusive.[26] Scholars like Bart Ehrman view the Gospel as a largely historically unreliable[dubious ] written account by an author posthumous to the Apostle who was not an eyewitness to the historical Jesus.[7][8][52][56][57][58][59] They also argue the traditional identification of the book's author, denoted in the text as the "beloved disciple", with the apostle John is false.[8][59] The Gospel was likely written c. 90-100, possibly in Ephesus.[28] Scholars[who?] who disagree with the traditional view believe it likely that John was martyred around the time James was, as suggested by Mark 10:39 and Acts 12:1-2.[8] The authorship of the Gospel continues to be debated, with the more conservative scholars concluding that the traditional historical view of John being the author is accurate. The issue of authorship is sometimes absorbed[who?] into the reconstruction of the Gospel's development over a period of time in various stages. It is thus more complex than simply identifying a single person as the document's author. Liberal experts do not accept that the Fourth Evangelist was an eyewitness to the historical Jesus.[60] Raymond E. Brown summarizes a prevalent theory regarding the development of this gospel.[61] He identifies three layers of text in the Fourth Gospel (a situation that is paralleled by the synoptic gospels):

Other modern viewsMarvin Meyer, a Chapman University scholar of religion, has argued that Mary Magdalene was not just companion and confidante of Jesus, but also his spokesperson, the disciple he most loved, possibly the Beloved Disciple mentioned in the Gospel of John, and the "author" or "primary source" for that gospel.[62][63] Ephesus in Asia Minor is a popular suggestion for the gospel's origin, which was the locale of both Mary and John.[5] Richard Bauckham, professor of New Testament at the University of St. Andrews, Scotland, presents his alternative approach to John. He has concluded that John’s gospel is an integral whole written by a single author—John the Elder, a Jerusalem disciple but not one of the Twelve, aka the Beloved Disciple. He is convinced that John’s gospel is not the product of, written for, or telling the story of a so-called “Johannine community”. Instead, it tells the story of Jesus for both believers and nonbelievers. It is intended for general circulation among all the churches. Bauckham claims that John’s gospel is a reliable source for the history of Jesus—at times even more so than the Synoptic gospels.[64] Bauckham's claims have come under dispute.[65][66] SourcesMissing partThe last verse of chapter 7 through verse 11 of chapter 8 in John's Gospel does not exist in the earliest extant manuscripts and thus may be a later interpolation. This is the passage concerning the woman taken in adultery, referred to as the pericope adulterae. Some Bible versions add it as a footnote, and some leave it out altogether including the Miniscule known as Minuscule 759 which omits verses 3-11. Some translations of the New Testament, however, include it as regular text. Order of materialAmong others, Rudolf Bultmann suggested[67] that the text of the gospel is partially out of order; for instance, chapter 6 should follow chapter 4[68]:

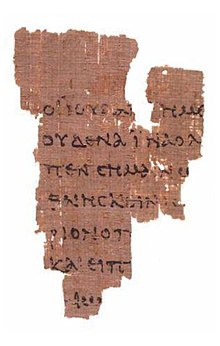

Chapter 5 deals with a visit to Jerusalem, and chapter 7 opens with Jesus again in Galilee since "he would not walk in Jewry, because the Jews sought to kill him" — a consequence of the incident in Jerusalem described in chapter 5. There are more proposed rearrangements. Signs gospelFurther information: Signs Gospel One possible construction of the "internal evidence" states that the Beloved Disciple wrote an account of the life of Jesus.[21:24] However, this disciple died unexpectedly, necessitating that a revised gospel be written.[21:23] It may be that John “is the source" of the Johannine tradition but "not the final writer of the tradition." [69] Therefore, scholars are no longer looking for the identity of a single writer but for numerous authors whose authorship has been absorbed into the gospel's development over a period of time and in several stages. [60][61][70] The hypothesis of the Gospel being composed in layers over a period of time had its start with Rudolf Bultmann in 1941. Bultmann suggested[67] that the author(s) of John depended in part on an author who wrote an earlier account. This hypothetical "Signs Gospel" listing Christ's miracles was independent of, and not used by, the synoptic gospels. It was believed to have been circulating before the year 70 AD. Bultmann's conclusion was so controversial that heresy proceedings were instituted against him and his writings. (See: Images of Jesus and more detailed discussions linked below.) Nevertheless, scholars such as Raymond Edward Brown continue to consider this hypothesis a plausible possibility. They believe the original author of the Signs Gospel to be the Beloved Disciple. They argue that the disciple who formed this community was both an historical person and a companion of Jesus Christ. Brown goes one step further by suggesting that the Beloved Disciple had been a follower of John the Baptist before joining Jesus.[61] Synoptic materialRaymond Brown and Paul Barnett believe that the Gospel was composed as an independent source from the synoptic gospels.[71][72] James Tabor describes the core narrative of John as "an independent account based on materials and testimony the authors (the “we” of 21:24) attribute to the mysterious unnamed “disciple whom Jesus loved,” who only shows up at the “last supper” and appears again at the crucifixion, the empty tomb, and up on the Sea of Galilee when the disciples had returned to their fishing.[73][74] Some scholars believe that the structure of John is similar enough to the structure of the synoptic gospels that the author had access to a synoptic gospel or to some other source close to the synoptics.[7][page needed] Specifically, the author seems to echo the distinctive style of Mark, and his Passion narrative resembles Luke's.[8][page needed] DiscoursesThe author may have used a source consisting of lengthy discourses,[75] but this issue has not been clarified.[7] InspirationThe author has Jesus foretell that new knowledge will come to his followers after his death.[76] This reference indicates that the author may have included new information, not previously revealed, that is derived from spiritual inspiration rather than from historical records or recollection.[76] The Trimorphic ProtennoiaMain article: Trimorphic Protennoia In terminology close to that found in later Gnostic works, one tract, generally known as "The Trimorphic Protennoia", must either be dependent on John or the other way round."[77] DateMain article: Dating the Bible There is no certain historical evidence as to the date of its composition. Scholars[who?] often date it to c. 80–95, decades after the events it describes.[5][78] Popular author and Biblical critic Bart Ehrman argues that there are differences in the composition of the Greek within the Gospel, such as breaks and inconsistencies in sequence, repetitions in the discourse, as well as passages that clearly do not belong to their context, and these suggest redaction.[79] The so-called "Monarchian Prologue" to the Fourth Gospel (c. 200) supports A.D. 96 or one of the years immediately following as to the time of its writing.[80] Scholars set a range of c. 90–100.[81] The gospel was already in existence early in the 2nd Century.[82] John was composed in stages (probably two or three).[83] There is credible evidence that the Gospel was written no later than the middle of the 2nd century. Since the middle of the 2nd century writings of Justin Martyr use language very similar to that found in the Gospel of John, the Gospel is considered to have been in existence at least at that time.[84] The Rylands Library Papyrus P52, which records a fragment of this gospel, is usually dated to the first half of the 2nd century.[85] Conservative scholars consider internal evidences, such as the lack of the mention of the destruction of the Temple and a number of passages that they consider characteristic of an eyewitness,[86][citation needed] sufficient evidence that the gospel was composed before 100 and perhaps as early as 50–70: in the 1970s, scholars Leon Morris and John A.T. Robinson independently suggested earlier dates for the gospel's composition.[87][88] The noncanonical Dead Sea Scrolls suggest an early Jewish origin, parallels and similarities to the Essene Scroll, and Rule of the Community.[89] Many phrases are duplicated in the Gospel of John and the Dead Sea Scrolls. These are sufficiently numerous to challenge the theory that the Gospel of John was the last to be written among the four Gospels[90] and that it shows marked non-Jewish influence.[91] Textual history and manuscripts The Rylands Papyrus is perhaps the earliest New Testament fragment; dated from its handwriting to about 125. Probably the earliest surviving New Testament manuscript, Rylands Library Papyrus P52 is a Greek papyrus fragment discovered in Egypt in 1920 (now at the John Rylands Library, Manchester). Although P52 has no more than 114 legible letters, it must come from a substantial codex book; as it is written on both sides in a generously scaled script, with John 18:31–33 on one side and 18:37–38 on the other. The surviving text agrees closely with that of the corresponding passages in the Gospel of John, but it cannot necessarily be assumed that the original manuscript contained the full Gospel of John in its canonical form. Metzger and Aland list the probable date for this manuscript as c. 125[92][93] but the difficulty of estimating the date of a literary text based solely on paleographic evidence must allow potentially for a range that extends from before 100 to well into the second half of the 2nd century. P52 is small, and although a plausible reconstruction can be attempted for most of the fourteen lines represented, the proportion of the text of the Gospel of John for which it provides a direct witness is so small that it is rarely cited[who?] in textual debate.[94][95] Other notable early manuscripts of John include Papyrus 66 and Papyrus 75, in consequence of which a substantially complete text of the Gospel of John exists from the beginning of the 3rd century at the latest. Hence the textual evidence for the Gospel of John is commonly accepted as both earlier and more reliable than that for any other of the canonical Gospels. Much current research on the textual history of the Gospel of John is being done by the International Greek New Testament Project. Egerton gospelThe mysterious Egerton Gospel appears to represent a parallel but independent tradition to the Gospel of John. According to scholar Ronald Cameron, it was originally composed some time between the middle of the 1st century and early in the 2nd century, and it was probably written shortly before the Gospel of John.[96] Liberal scholar Robert W. Funk and the Jesus Seminar place the Egerton fragment in the 2nd century, perhaps as early as 125, which would make it as old as the oldest fragments of John.[97] Position in the New TestamentIn the standard order of the canonical gospels, John is fourth, after the three interrelated synoptic gospels Matthew, Mark and Luke. In the earliest surviving gospel collection, Papyrus 45 of the 3rd century, it is placed second in the order Matthew, John, Luke and Mark, an order which is also found in other very early New Testament manuscripts. In syrcur it is placed third in the order Matthew, Mark, John and Luke.[98] Narrative summary (structure and content)

After the prologue,[Jn 1:1–5] the narrative of the gospel begins with verse 6, and consists of two parts. The first part[1:6-12:50] relates Jesus' public ministry from John the Baptist recognizing him as the Lamb of God to the raising of Lazarus and Jesus' final public teaching. In this first part, John emphasizes seven of Jesus' miracles, always calling them "signs." The second part[13–21] presents Jesus in dialogue with his immediate followers[13–17] and gives an account of his Passion and Crucifixion and of his appearances to the disciples after his Resurrection.[18–20] In the "appendix",[21] Jesus restores Peter after his denial, predicts Peter's death, and discusses the death of the "beloved disciple". Raymond E. Brown, a scholar of the social environment where the Gospel and Letters of John emerged, labeled the first and second parts the "Book of Signs" and the "Book of Glory", respectively.[99] Hymn to the WordThis prologue is intended to identify Jesus as the eternal Word (Logos) of God.[17] Thus John asserts Jesus' innate superiority over all divine messengers, whether angels or prophets.[5] Here John adapts the doctrine of the Logos, God's creative principle, from Philo, a 1st-century Hellenized Jew.[5] Philo had adopted the term Logos from Greek philosophy, using it in place of the Hebrew concept of Wisdom (sophia) as the intermediary (angel) between the transcendent Creator and the material world.[5] Some scholars argue that the prologue was taken over from an existing hymn and added at a later stage in the gospel's composition.[17] Seven SignsThis section recounts Jesus' public ministry.[17] It consists of seven miracles or "signs," interspersed with long dialogues and discourses, including several "I am" sayings.[5] The miracles culminate with his most potent, raising Lazarus from the dead.[5] In John, it is this last miracle, and not the temple incident, that prompts the authorities to have Jesus executed.[5] Last teachings and deathThis section opens with an account of the Last Supper that differs significantly from that found in the synoptics.[5] Here, Jesus washes the disciples feet instead of ushering in a new covenant of his body and blood.[5] This account of foot washing might refer to a local tradition by which foot washing served as a Christian initiation ritual rather than baptism.[100] John then devotes almost five chapters to farewell discourses.[5] Jesus declares his unity with the Father, promises to send the Paraclete, describes himself as the "real vine," explains that he must leave (die) before the Holy Spirit comes, and prays that his followers be one.[5] The farewell discourses resemble farewell speeches called testaments, in which a father or religious leader, often on the deathbed, leaves instructions for his children or followers.[101] Verses 14:30-31 represent a conclusion, and the Jesus Seminar says the next three chapters were inserted later[101] and the discourses assembled over time, representing the theology of the "Johannine circle" more than the message of the historical Jesus.[101] John then records Jesus' arrest, trial, execution, and resurrection appearances, including "doubting Thomas."[5] Significantly, John does not have Jesus claim to be the Son of God or the Messiah before the Sanhedrin or Pilate, and he omits the traditional earthquakes, thunder, and midday darkness that were said to accompany Jesus' death.[5] John's revelation of divinity is Jesus' triumph over death, the eighth and greatest sign.[5] Chapter 21, in which the "beloved disciple" claims authorship, is commonly assumed to be an appendix, probably added to allay concerns after the death of the beloved disciple.[5] There had been a rumor that the End would come before the beloved disciple died.[102] Detailed contentsThe major events covered by the Gospel of John include: Characteristics of the Gospel of JohnThough the three Synoptic Gospels share a considerable amount of text, over 90% of John's Gospel is unique to him.[103] The synoptics describe much more of Jesus' life, miracles, parables, and exorcisms. However, the materials unique to John are notable, especially in their effect on modern Christianity. As a gospel, John is a story about the life of Jesus. The Gospel can be divided into four parts: The Prologue[Jn. 1:1-18] is a hymn identifying Jesus as the Logos and as God. The Book of Signs [1:19-12:50] recounts Jesus' public ministry, and includes the signs worked by Jesus and some of his teachings. The Passion narrative[13-20] recounts the Last Supper (focusing on Jesus' farewell discourse), Jesus' arrest and crucifixion, his burial, and resurrection. The Epilogue[John 21] records a resurrection appearance of Jesus to the disciples in Galilee. Following on from "the higher criticism" of the 19th century, Adolf von Harnack[105] and Raymond E. Brown[61] have questioned the gospel of John as a reliable source of information about the historical Jesus.[106][107] ChristologyJohn portrays Jesus Christ as "a brief manifestation of the eternal Word, whose immortal spirit remains ever-present with the believing Christian."[108] The book presents Jesus as divine and yet subordinate to the one true God.[109] The gospel gives far more focus to the relationship of the Son to the Father than the other gospels and it has often been used in the Christian development and understanding of the Trinity. John includes far more direct claims of Jesus being a Son of God than the Synoptic Gospels. The gospel also focuses on the relation of the Redeemer to believers, the announcement of the Holy Spirit as the Comforter (Greek Paraclete), and the prominence of love as an element in the Christian character. Jesus' divine roleIn the synoptics, Jesus speaks often about the Kingdom of God; his own divine role is obscured (see Messianic secret). In John, Jesus talks openly about his divine role. He says, for example, that he is the way, the truth, and the life. He echoes Yahweh's own statements with several "I am" declarations that also identify him with symbols of major significance:[110]

Critical scholars think that these claims represent the Christian community's faith in Jesus' divine authority but doubt that the historical Jesus actually made these sweeping claims.[5] Other scholars have argued that the "I Am" statements are in reference to YHWH, and have interpreted John 12:44 as meaning that Jesus expressly denied being God.[111] John also promises eternal life for those who believe in Jesus.[3:16 and others] LogosMain article: Logos In the Prologue, John identifies Jesus as the Logos (Word). A term from Greek philosophy, it meant the principle of cosmic reason. In this sense, it was similar to the Hebrew concept of Wisdom, Yahweh's companion and intimate helper in creation. The Jewish philosopher Philo merged these two themes when he described the Logos as God's creator of and mediator with the material world. The evangelist adapted Philo's description of the Logos, applying it to Jesus, the incarnation of the Logos.[8] The opening verse of John is translated as "the Word was with God and the Word was God" in all orthodox and historical Bibles.[112][citation needed] There are alternative views. The explicit statement that Jesus was himself the Arche does not come from John's gospel but from the Letter to the Colossians.[Col. 1:18][citation needed] The Scholar's Version of the gospel, developed by the Jesus Seminar, loosely translates the phrase as "The Logos was what God was," offered as a better representation of the original meaning of the evangelist.[113] John the BaptistMain article: John the Baptist John's account of the Baptist is different from that of the synoptic gospels. John is not called "the Baptist."[17] John's ministry overlaps with Jesus', his baptism of Jesus is not explicitly mentioned, but his witness to Jesus is unambiguous.[17] The evangelist almost certainly knew the story of John's baptism of Jesus and he makes a vital theological use of it.[114] He subordinates John to Jesus, perhaps in response to members of the Baptist's sect who denied Jesus' superiority.[5] In John, Jesus and his disciples go to Judea early in Jesus' ministry when John has not yet been imprisoned and executed by Herod. He leads a ministry of baptism larger than John's own. The Jesus Seminar rated this account as black, containing no historically accurate information.[113] Historically, John likely had a larger presence in the public mind than Jesus.[115] JewsMain article: Antisemitism in the New Testament In his Jerusalem speeches, John's Jesus makes unfavorable references to the Jews.[8] These references may constitute a rebuttal on the part of the author against Jewish criticism of the early Church.[8] The author likely considered himself Jewish, did not deny that Jesus and his disciples were all Jewish, and was probably speaking to a largely Jewish community.[116] While passages in John have used to support anti-semitism, these passages reflect a dispute within Judaism, and it's highly questionable whether the evangelist himself was anti-semitic.[117] Gnostic elementsSee also: Gnosticism Though not commonly understood as Gnostic, John has elements in common with Gnosticism.[5] Christian Gnosticism did not fully develop until the mid-2nd century and second-century Christians concentrated much effort in examining and refuting it.”[118] To say John’s Gospel contained elements of Gnosticism is to assume that Gnosticism had developed to a level that required the author to respond to it.[119] Comparisons to Gnosticism are based not in what the author says, but in the language he uses to say it, notably, use of the concepts of Logos and Light.[120] Gnostics read John but interpreted it differently than non-Gnostics.[121] Gnosticism taught that salvation came from gnosis, secret knowledge, and Gnostics did not see Jesus as a savior but a revealer of knowledge.[122] Raymond Brown contends that "The Johannine picture of a savior who came from an alien world above, who said that neither he nor those who accepted him were of this world,[17:14] and who promised to return to take them to a heavenly dwelling[14:2-3] could be fitted into the gnostic world picture (even if God's love for the world in 3:16 could not)."[123] It has been suggested that similarities between John's Gospel and Gnosticism may spring from common roots in Jewish Apocalyptic literature.[124] Historical reliability of JohnThe teachings of Jesus in John are very different from those found in the synoptic gospels.[76] Thus, since the 19th century scholars[who?] have generally believed that only one of the two traditions could be authentic.[76] J. D. G. Dunn comments, "Few scholars would regard John as a source for information regarding Jesus' life and ministry in any degree comparable to the synoptics."[58][125] E. P. Sanders concludes that the Gospel of John contains an "advanced theological development, in which meditations of the person and work of Jesus are presented in the first person as if Jesus said them."[126] The scholars of the Jesus Seminar identify the historical inferiority of John as foundational to modern gospel scholarship.[59] Geza Vermes discounts all the teaching in John when reconstructing "the authentic gospel of Jesus."[127] The Gospel of John also differs from the synoptic gospels in respect of its narrative of Jesus' life and ministry; but here there is a lower degree of consensus that the synoptic tradition is to be preferred. John A.T. Robinson says that, where the Gospel narrative accounts can be checked for consistency with surviving material evidence, the account in the Gospel of John is commonly the more plausible;[128] that it is generally easier to reconcile the various synoptic accounts within John's narrative framework, than it is to explain John's narrative within the framework of any of the synoptics;[129] and that, where in the Gospel Jesus and his disciples are described as travelling around identifiable locations, the trips in question can always be plausibly followed on the ground,[130] which he says is not the case for any synoptic Gospel. John is not entirely without historical value. Critical scholarship in the 19th century distinguished between the "biographical" approach of the synoptics and the "theological" approach of John, and accordingly tended to disregard John as a historical source. This distinction is no longer regarded as sustainable in more recent scholarship, which emphasizes that all four gospels are both biographical and theological. According to Barnabas Lindars, "All four Gospels should be regarded primarily as biographies of Jesus, but all four have a definite theological aim."[131] Sanders points out that the author would regard the gospel as theologically true as revealed spiritually even if its content is not historically accurate.[126] The gospel does contain some independent, historically plausible elements.[132] Theissen and Thompson think that Jesus was executed before Passover, as John reports.[132][133] Henry Wansbrough says: "Gone are the days when it was scholarly orthodoxy to maintain that John was the least reliable of the gospels historically." It has become generally accepted that certain sayings in John are as old or older than their synoptic counterparts, that John's knowledge of things around Jerusalem is often superior to the synoptics, and that his presentation of Jesus' agony in the garden and the prior meeting held by the Jewish authorities are possibly more historically accurate than their synoptic parallels.[134] And Thompson writes, "There are items only in John that are likely to be historical and ought to be given due weight. Jesus' first disciples may once have been followers of the Baptist (cf. Jn. 1:35-42). There is no a priori reason to reject the report of Jesus and his disciples' conducting a ministry of baptism for a time.[3:22-26] That Jesus regularly visited Jerusalem, rather than merely at the time of his death, is often accepted as more realistic for a pious, 1st-century Jewish male (and is hinted at in the other Gospels as well: Mark 11:2; Luke 13:34; 22:8-13,53) ... Sanders, however, cautions that even historically plausible elements in John can hardly be taken as historical evidence, as they may well represent the author's intuition rather than historical recollection.[126] Development of the gospelSome scholars today believe that parts of John represent an independent historical tradition from the synoptics, while other parts represent later traditions.[71] The Gospel was probably shaped in part by increasing tensions between synagogue and church, or between those who believed Jesus was the Messiah and those who did not.[135] The chronology of Jesus' ministry in JohnMain article: Chronology of Jesus A distinctive feature of the Gospel of John, is that it provides a very different chronology of Jesus' ministry from that in the synoptics. E.P. Sanders suggests that John's chronology, even when ostensibly more plausible, should nevertheless be treated with suspicion on the grounds that the Synoptic accounts are otherwise superior as historic sources. C.H. Dodd proposes that historians may mix and match between John and the synoptics on the basis of whichever appears strongest on a particular episode. Robinson says that John's chronology is consistently more likely to represent the original sequence of events. Robinson offers three arguments for preferring the chronology of John's Gospel to that of the synoptics. First, he argues that John's account of Jesus' ministry is always consistent, in that seasonal references always follow in the correct sequence, geographical distances are always consistent with indications of journey times, and references to external events always cohere with the internal chronology of Jesus' ministry. He claims that the same cannot be claimed for any of the three Synoptic accounts. For example, the harvest-tide story of Mark 2:23 is shortly followed by reference to green springtime pasture at 6:39. Again, the historically consistent reference to the period of the temple construction in John 2:20, may be contrasted with the impossibility of reconciling Luke's account of the census of Luke 2:2 with historic records of Quirinius's governorship of Syria. Second, Robinson appeals to the critical principle, widely applied in textual study, that the account is most likely to be original that best explains the other variants. He argues that would be relatively easy to have created the Synoptic chronology by selecting and editing from John's chronology; whereas expanding the Synoptic chronology to produce that found in John, would have required a wholescale rewriting of the sources. Third, Robinson claims that elements consistent with John's alternative chronology can be found in each of the Synoptic accounts, whereas the contrary is never the case. Hence, Mark's explicit claim that the Last Supper was a Passover meal is contraindicated by his statement that Joseph of Arimathea bought a shroud for Jesus on Good Friday; which would not have been possible if it were a festival day. A two-year ministryIn John's Gospel, the public ministry of Jesus extends over rather more than two years. At the start of his ministry Jesus is in Jerusalem for Passover,[Jn 2:13] then he is in Galilee for the following Passover,[6:4] before going up to Jerusalem again for his death at a third Passover.[11:35] The synoptics by contrast only explicitly mention the final Passover, and their accounts are commonly understood as describing a public ministry of less than a year. In favour of the Synoptic chronology, E.P Sanders observes that a short ministry accords with the careers of other known prophetic figures of the time─who appear in the desert, raise large scale public interest, but soon come to a bloody end at the hand of the Roman military. In favour of the two-year ministry, John Robinson points out that both Matthew and Luke imply that Jesus was preaching in Galilee for at least one Passover during his ministry. The Temple tax[Jn 17:24] is only collected at Passover; moreover, the massacred Galileans of Luke 13:1 would appear to have been in Jerusalem for Passover, as this was the only pilgrim feast where the faithful slaughtered their animals themselves. The cleansing of the TempleMain article: Jesus and the money changers In John, Jesus drives the money changers from the Temple at the start of his ministry, whereas in the Synoptic account this occurs at the end, immediately after Palm Sunday. In favor of the later dating of the synoptics, Geza Vermes says that this event provides a clear context and pretext for Jesus' arrest, trial and execution. It makes more sense to suppose that events proceeded quickly. Robinson says that all three Synoptic accounts explain the reluctance of the Temple authorities to arrest Jesus on the spot, as being due to their fear of popular support for John the Baptist. This would make more sense while the Baptist was still alive. An earlier baptizing ministry in JudeaIn chapters 3 and 4 of the Gospel of John, Jesus, following his encounter with John the Baptist, undertakes an extended and successful baptizing ministry in Judea and on the banks of the River Jordan; initially as an associate of the Baptist, latterly more as a rival. In the Synoptic accounts, Jesus retreats into the wilderness following his baptism, and is presented as gathering disciples from scratch in his home country of Galilee; following which he embarks on a ministry of teaching and healing, in which baptism plays no part. In favour of the Synoptic account is the clear characterisation of Jesus and his disciples in all the Gospels as predominantly Galilean. Against this, Robinson points out that all the synoptics are agreed that, when Jesus arrives in Jerusalem in the week before his death, he already has a number of followers and disciples in the city, notably Joseph of Arimathea. and the unnamed landlord of the upper room, who knows Jesus as 'the Master'. Repeated visits to JerusalemIn John, Jesus not only starts his ministry in Jerusalem, he returns there for other festivals, notably at John 5:1 and at 7:2. As noted above, E.P Sanders regards the short, sharp prophetic career as having greater verisimilitude. Against this John Robinson notes the numerous instances in the Synoptic account of Jesus' final days in Jerusalem, when it is implied that he has been there before. In two of the synoptics (Matthew 23:37 and Luke 13:34), Jesus appears to recall several previous preaching ministries in Jerusalem, when his message had nevetheless been generally spurned. The date of the crucifixionIn the Jewish calendar, each day runs from sunset to sunset, and hence the Last Supper (on the Thursday evening), and Jesus's crucifixion (on Friday afternoon), both fell on the same day. In John, this day was the 14th of Nisan in the Jewish calendar; that is the day on the afternoon of which the Passover victims were sacrificed in the Temple, which was also known as the Day of Preparation. The Passover meal itself would then have been eaten on the Friday evening (i.e. the next day in Jewish terms), which would also have been a Sabbath. In the Synoptic accounts, the Last Supper is a Passover meal, and so Jesus's trial and crucifixion must have taken place during the night time and following afternoon of the festival itself, the 15th of Nisan. In favour of the Synoptic chronology is that in the earliest Christian traditions relating to the Last Supper in the first letter of Paul to the Corinthians, there is a clear link between Passion of Jesus, the Last Supper and the Passover lamb. In favor of John's chronology is the near universal modern scholarly agreement that the Synoptic accounts of a formal trial before the Sanhedrin on a festival day are historically impossible. By contrast, an informal investigation by the High Priest and his cronies (without witnesses being called), as told by John, is both historically possible in an emergency on the day before a festival, and accords with the external evidence from Rabbinic sources that Jesus was put to death on the Day of Preparation for the Passover. Astronomical reconstruction of the Jewish Lunar calendar tends to favor John's chronology, in that the only year during the governorship of Pontius Pilate when the 15th Nisan is calculated as falling on a Wednesday/Thursday was 27 CE, which appears too early as the year of the crucifixion, whereas the 14th of Nisan fell on a Thursday/Friday in both 30 CE and 33 CE. John and the synoptics comparedJohn is significantly different from the Synoptic Gospels:

Comparison Chart of the Major GospelsThe material in the Comparison Chart is from the Gospel Parallels by B. H. Throckmorton, The Five Gospels by R. W. Funk, The Gospel According to the Hebrews, by E. B. Nicholson & The Hebrew Gospel and the Development of the Synoptic Tradition by J. R. Edwards.

HistoryJohn was written somewhere near the end of the 1st century, probably in Ephesus, in Anatolia. The tradition of John the Apostle was strong in Anatolia, and Polycarp of Smyrna reportedly knew him. Like the previous gospels, it circulated separately until Irenaeus proclaimed all four gospels to be scripture.[178] The Church Fathers Polycarp, Ignatius of Antioch, and Justin Martyr did not mention this gospel, either because they did not know it or did not approve of it.[140] In the 2nd century, the two main, conflicting expressions of Christology were John's Logos theology, according to which Jesus was the incarnation of God's eternal Word, and adoptionism, according to which Jesus was "adopted" as God's Son. Christians who rejected Logos Christology were called "Alogi," and Logos Christology won out over adoptionism. The Gospel of John was the favorite gospel of Valentinus, a 2nd-century Gnostic leader.[140] His student Heracleon wrote a commentary on the gospel, the first gospel commentary in Christian history.[140] In the Diatesseron, the content of John was merged with the content of the synoptics to form a single gospel that included nearly all the material in the four canonical gospels. When Irenaeus proposed that all Christians accept Mark, Matthew, Luke, and John as orthodox, and only those four gospels, he regarded John as the primary gospel, due to its high Christology.[140] Jerome translated John into its official Latin form, replacing various older translations. Although harmonious with the Synoptic Gospels and probably primitive (the Didascalia Apostolorum definitely refers to it and it was probably known to Papias), the Pericope Adulterae is not part of the original text of the Gospel of John.[179] Zane C. Hodges says, "If it is not an original part of the Fourth Gospel, its writer would have to be viewed as a skilled Johannine imitator, and its placement in this context as the shrewdest piece of interpolation in literary history!"[180] RepresentationsThe Gospel of John has influenced Impressionist painters, Renaissance artists and classical art, literature and other depictions of Jesus, with influences in Greek, Jewish and European history. It has been depicted in live narrations and dramatized in productions, skits, plays, and passion plays, productions, as well as on film. The most recent film portrayal being that of 2003's 'The Visual Bible: The Gospel of John', directed by Philip Saville and narrated by Christopher Plummer, and starring Henry Ian Cusick as Jesus. See also

References

Notes

External links

Online translations of the Gospel of John:

Related articles:

Disculpen las Molestias

Sri Garga-Samhita | Oraciones Selectas al Señor Supremo | Devotees Vaishnavas | Dandavat pranams - All glories to Srila Prabhupada | Hari Katha | Santos Católicos | JUDAISMO | Buddhism | El Mundo del ANTIGUO EGIPTO II | El Antiguo Egipto I | Archivo Cervantes | Sivananda Yoga | Neale Donald Walsch | SWAMIS jueves 11 de marzo de 2010ENCICLOPEDIA - INDICE | DEVOTOS FACEBOOK | EGIPTO - USUARIOS de FLICKR y PICASAWEBOtros Apartados

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Archivo del blog

-

▼

2010

(40)

-

▼

octubre

(40)

- Categoría:Manuscritos de Nag Hammadi

- Discurso sobre la Ogdóada y la Eneada

- Evangelio de Tomás - Gospel of Thomas

- Nuevo Testamento - New Testament

- Evangelio de Juan - Gospel of John

- Evangelio de Lucas - Gospel of Luke

- Evangelio de Mateo - Gospel of Matthew

- Evangelio de Marcos - Gospel of Mark

- Tratado de la Resurrección

- Tratado Tripartito - Tripartite Tractate

- Apócrifos - Biblical apocrypha

- Gnosticismo - Gnosticism

- Evangelio de Valentín - Gospel of Truth

- Apócrifo de Santiago - Apocryphon of James

- Oración de Pablo - Prayer of the Apostle Paul

- Manuscritos de Nag Hammadi

- Evangelio apócrifo

- Diccionarios de la Biblia - Xabier Pikaza

- tablas

- Tablas de Arqueología - Antipatris - Arqueología

- Ivory and gold in the Delta: excavations at Tell e...

- Indice de Nombres Propios y Temas III - DICCIONARI...

- Indice de Nombres Propios y Temas II - DICCIONARIO...

- URA - ZOAN - DICCIONARIO BIBLICO ARQUEOLOGICO

- TELL ARAQ EL MENSHIYEH - UMMA - DICCIONARIO BIBLIC...

- SINAI - TELL ARPACHIYA - DICCIONARIO BIBLICO ARQU...

- ROSETA, PIEDRA - SINAGOGA - DICCIONARIO BIBLICO A...

- PALERMO, LA PIEDRA DE - ROMA - DICCIONARIO BIBLICO...

- MOAB, MOABITAS - PALEONTOLOGÍA - DICCIONARIO BIBLI...

- LIBRO DE LOS MUERTOS, EL - MIZPA - DICCIONARIO BIB...

- JERICO (NUEVO TESTAMENTO) - LEY, MESOPOTAMICA - DI...

- HABACUC, COMENTARIO DE - JERICO (ANTIGUO TESTAMENT...

- FERTIL MEDIA LUNA - GUERRA - DICCIONARIO BIBLICO ...

- EFESO - FENICIA, FENICIOS - DICCIONARIO BIBLICO A...

- CASITAS - EDOM, EDOMITAS - DICCIONARIO BIBLICO AR...

- BABILONIA, LAS CRONICAS DE - CARRHAE - DICCIONARIO...

- ARQUITECTURA - BABILONIA - DICCIONARIO BIBLICO AR...

- ANTIPATRIS, AFEC - ARQUEOLOGÍA - DICCIONARIO BIBLI...

- ABGAR - ANTIOQUIA (DE SIRIA) - DICCIONARIO BIBLICO...

- LEYENDA DE ADAPA

-

▼

octubre

(40)

Datos personales

lunes, 25 de octubre de 2010

Evangelio de Juan - Gospel of John

Suscribirse a:

Enviar comentarios (Atom)

No hay comentarios:

Publicar un comentario