Evangelio de MarcosDe Wikipedia, la enciclopedia libre El Evangelio según Marcos (en griego, εὐαγγέλιον κατὰ Μᾶρκον) o Evangelio de Marcos (abreviado, Mc) es el segundo libro del Nuevo Testamento de la Biblia cristiana. Es el más breve de los cuatro evangelios canónicos y también el más antiguo según la opinión mayoritaria de los expertos bíblicos.[1] [2]Entre los estudiosos existe un amplio consenso en datar el Evangelio de Marcos a finales de los años 60 del siglo I d.C., o poco después del año 70 d.C.[3] Su autor es desconocido, aunque una tradición cristiana tardía lo atribuye a Marcos, personaje citado en otros pasajes del Nuevo Testamento. Narra la vida de Jesús de Nazaret desde su bautismo por Juan el Bautista hasta su "resurrección".

[editar] El evangelio de Marcos y el problema sinópticoExiste una estrecha relación entre los tres evangelios sinópticos (Marcos, Mateo y Lucas). De los 662 versículos que componen el Evangelio de Marcos,406 son comunes tanto con Mateo como con Lucas, 145 sólo con Mateo y 60 sólo con Lucas. Únicamente 51 versículos de Marcos no tienen paralelo en ninguno de los otros dos sinópticos.La tradición cristiana había establecido que el evangelio más antiguo era el de Mateo. Se había llegado a afirmar que el de Marcos era un resumen de los evangelios de Mateo y Lucas. Weisse y Wilke, de modo independiente, en 1838 concluyeron que el evangelio de Marcos no era un resumen de Mateo y Lucas, sino que era anterior a ellos y más bien les había servido de fuente. Además, Weisse estableció la teoría de que existía una fuente común a Mateo y Lucas. Johannes Weiss, en 1890, denominó con la letra Q a esta fuente (de Quelle, que significa ‘fuente’ en alemán). La teoría de las dos fuentes fue analizada y sistematizada por Heinrich Julius Holtzmann. La hipótesis más extendida para explicar la relación entre Marcos y los otros dos evangelios sinópticos, Mateo y Lucas, es hoy la teoría de las dos fuentes. Esto no quiere decir que todos los expertos la acepten, ni que no puedan oponérsele diversas objeciones. Hay bastante acuerdo, sin embargo, en que Marcos fue el primero de los cuatro evangelios en ser redactado. En el marco de la teoría de las dos fuentes, las posibles relaciones entre el evangelio de Marcos y la fuente Q han sido estudiadas por autores como L. Burton Mack (The Lost Gospel: The Book of Q and Christian origins, 1993) y Udo Schnelle (The History and Theology of the New Testament Writings, 1998). [editar] Autoría[editar] Atribución a MarcosNo existen pruebas definitivas acerca de quién fue el autor de este evangelio. El texto no incluye ninguna indicación sobre su autoría.La tradición cristiana, sin embargo, ha atribuido el evangelio a Marcos, discípulo de Pedro personaje citado en las epístolas de Pablo de Tarso (concretamente en Col 4,10), en los Hechos de los apóstoles (Hch 12,12-25; Hch 13,15; Hch 15,37), donde es presentado como compañero de Pablo.[4] y en la primera epístola de Pedro, que lo llama "mi hijo" (1 Pedro 5:13) La base de esta tradición se encuentra en algunas referencias de los primitivos autores cristianos a la idea de que Marcos puso por escrito los recuerdos del apóstol Pedro. Eusebio de Cesarea, que escribió a comienzos del siglo IV, cita en su Historia eclesiástica un fragmentos de la obra hoy perdida de Papías de Hierápolis, de comienzos del siglo II.[5] Papías, a su vez, remonta su testimonio a Juan el Presbítero. y el anciano decía lo siguiente: Marcos, que fue intérprete de Pedro, escribió con exactitud todo lo que recordaba, pero no en orden de lo que el Señor dijo e hizo. Porque él no oyó ni siguió personalmente al Señor, sino, como dije, después a Pedro. Éste llevaba a cabo sus enseñanzas de acuerdo con las necesidades, pero no como quien va ordenando las palabras del Señor, más de modo que Marcos no se equivocó en absoluto cuando escribía ciertas cosas como las tenía en su memoria. Porque todo su empeño lo puso en no olvidar nada de lo que escuchó y en no escribir nada falso Hacia el año 180, Ireneo de Lyon, escribió:Eusebio, Hist. Ecl. III 39. Tras su partida [la muerte de Pablo y Pedro], Marcos, discípulo e intérprete de Pedro, recogió por escrito lo que había sido predicado por Pedro El apologista Justino Mártir cita una información que se encuentra también en el Evangelio de Marcos diciendo que son las memorias de Pedro (Dial. 106.3).[6] En Hechos 10:34-40, el discurso de Pedro resume las líneas generales del Evangelio de Marcos. Por otro lado, no parece haber ninguna razón por la cual los primitivos cristianos tuvieran que adjudicar la autoría de este evangelio a un personaje oscuro que no fue discípulo directo de Jesús, en lugar de atribuírsela a uno de los apóstoles.Ireneo, Adversus Haereses 3.1.1 Algunos autores actuales[7] consideran sumamente dudosa la atribución a Marcos, dado que la teología de este evangelio parece más cercana a las ideas de Pablo de Tarso que a las de Pedro, que sale bastante malparado en el relato marcano. Tanto los errores del autor en cuestiones referentes a la geografía palestinense como lo que se sabe del proceso de composición de la obra no parecen abonar la teoría de la escritura de este evangelio por un discípulo directo de Pedro. Parece demostrado que antes de la escritura de este evangelio circulaban ya oralmente breves relatos sobre Jesús y sus dichos ("perícopas"), y que el autor recopiló estos materiales heterogéneos.[2] [editar] Indicios textuales sobre la autoríaEl autor, se trate o no de Marcos, parece ser que se dirige predominantemente a pagano-cristianos, más que a judeocristianos.[8] Cada vez que emplea un término en hebreo o en arameo, lo traduce al griego, lo que hace suponer que se dirige a una audiencia no familiarizada con estos idiomas. Utiliza la traducción al griego de la Biblia, la Biblia de los Setenta, y no su versión original hebrea, y no está familiarizado con la geografía de Palestina.[editar] Citas de la Biblia griegaEl evangelista utiliza en algunas de sus citas y expresiones la versión griega de la Biblia, en lugar de usar la versión hebrea o aramea, como sería de esperar en un judío originario de Judea.

[editar] Errores geográficosSe han señalado errores de bulto en los itinerarios de Jesús que consigna en su relato: por ejemplo, en Marcos 7:31 afirma que Jesús se dirige desde Tiro hacia el mar de Galilea atravesando Sidón y la Decápolis, un itinerario geográficamente absurdo. Sin embargo, es posible que este itinerario tenga un fin catequético, pues Tiro, Sidón y la Decápolis eran territorio pagano y, el autor, pudo pretender simbolizar que el mensaje de Jesús estaba abierto también a los paganos.En un pasaje en el que relata un sorprendente exorcismo(Marcos 5:1-13), ubica la región de los gerasenos en la orilla oriental del lago de Genesaret, en la Decápolis. Pero la ciudad de Gerasa (hoy Jerash) se encuentra en realidad a más de 50 km del mismo. Mateo cambia la región de los gerasenos por la región de los gadarenos. Algunos autores (Frédéric Manns) describen que el nombre de Gerasa se presta a un juego de palabras en arameo, que hace pensar en que ya el texto arameo que usa Marcos utiliza el nombre de esta población. Así, en Mc 5,4 «romper (garas) las cadenas», en Mc 5,10 y Mc 5,17 «echar fuera (garash)», en Mc 5,20 «predicar (garashah)». Este relato pertenece al material común a Mateo, Marcos y Lucas (Lucas repite el error de Marcos, pero Mateo, como se ha dicho, cambia "Gerasenos" por "Gadarenos"). De todas formas, el texto no dice "Gerasa" sino "región de los gerasenos", lo cual puede ser como, por ejemplo, ubicar una escena en Móstoles y llamarlo "región de los madrileños". Es casi seguro que el relato sea simbólico (se considera una alegoría de la ocupación romana) y, por esta razón, probablemente el autor utilizó una ambigua alusión a la región de los gerasenos sin precisar el lugar, con el fin de que el relato no pueda ser desmentido. [editar] Errores en cuanto a costumbres judías

[editar] Expresiones y giros semíticosEl texto del evangelio de Marcos tiene abundantes expresiones semíticas. Para algunos autores, esto sería indicio de que se basa en un texto arameo (o varios textos, según teorías modernas). Destacan los siguientes:

[editar] Lugar de composiciónDesde la época de Clemente de Alejandría, a finales del siglo II, se había creído que este evangelio fue escrito en Roma, basándose en los latinismos que aparecen en el texto, como denarius o legion. Algunos de los latinismos empleados por Marcos que no aparecen en los otros evangelios son "σπεκουλατορα" ("speculatora", soldados de la guardia, Marcos 6:27), "ξεστων" (corrupción de "sextarius", vaso, Marcos 7:4) o "κεντυριων" ("centurión", Marcos 15:39, Marcos 15:44-45).Sin embargo, la hipótesis del origen romano del evangelio de Marcos fue cuestionada por autores como Reginald Fuller (A Critical Introduction to the New Testament), dado que los latinismos presentes en el evangelio marcano suelen ser términos relacionados con la vida militar, por lo que eran muy probablemente palabras conocidas en todas las regiones del Imperio Romano en las que existían guarniciones militares. Se ha propuesto como alternativa la posibilidad de que fuese redactado en Antioquía. Sin embargo, no existen indicios claros acerca del lugar donde fue compuesto el evangelio de Marcos. [editar] DestinatariosLa idea más extendida es que el evangelio de Marcos fue escrito para una comunidad cristiana helenística de lengua griega radicada en algún lugar del Imperio Romano. Parece que los destinatarios de este evangelio desconocían las tradiciones judías, ya que en varios pasajes el autor las explica (Marcos 7:1-4, Marcos 14:12, Marcos 15:42). También desconocían probablemente el arameo, ya que se traducen al griego las frases ταλιθα κουμ ("talitha kum", Marcos 5:41) αββα ("abba", Marcos 14:36), y el hebreo, que también se traduce κορβαν ("Corban", Marcos 7:11).Las citas del Antiguo Testamento proceden en general de la Biblia de los Setenta, traducción al griego (Marcos 1:2, Marcos 2:23-28, Marcos 12:18-27). Marcos 5:41 Marcos 5:41 Además, en el evangelio es perceptible una cierta actitud antijudía en la caracterización de los fariseos, o en la atribución a los miembros del Sanedrín, más que a las autoridades romanas, de la responsabilidad de la muerte de Jesús. Si se acepta la hipótesis de que el texto fue redactado en una fecha temprana y si se da por hecho que el autor es Marcos es posible que:

[editar] Fecha de composiciónVer artículo principal: Datación del Evangelio de MarcosLa mayoría de los estudiosos bíblicos[9] [10] data la redacción de este evangelio, en su estado actual, entre los años 65 y 75. El año 65 como terminus a quo se debe a dos motivos, fundamentalmente: por un lado, de acuerdo con lo mayoritariamente aceptado sobre el proceso de composición de este evangelio, se requirió cierto tiempo para que se desarrollasen las diferentes tradiciones orales sobre Jesús (perícopas) que se cree el autor de Marcos utilizó para la confección de su obra. En segundo lugar, se cree que ciertos pasajes del texto reflejan los acontecimientos de la Primera Guerra Judía, según se conocen por otras fuentes, especialmente las obras de Flavio Josefo, aunque se discute si la destrucción del Templo de Jerusalén (que tuvo lugar en el año 70) se había producido ya o se consideraba próxima. Los eruditos que consideran que ya se había producido basan su opinión sobre todo en el análisis del capítulo decimotercero de Marcos (Mc 13), conocido como "Apocalipsis Sinóptico" o "Pequeño Apocalipsis de Marcos", y en algunos otros fragmentos. El año 80 es considerado mayoritariamente el terminus ad quem para la adaptación de este evangelio, ya que, en el marco de la teoría de las dos fuentes, se cree que Marcos es el evangelio más antiguo, y que fue utilizado como fuente por Mateo y Lucas, escritos, según se cree, entre los años 80 y 100. Varios autores consideran que lo más probable es que fuese compuesto antes del año 68, año del martirio de Marcos en Alejandría. Algunos eruditos, sin embargo, han propuesto una revisión radical de esta cronología: algunos de ellos proponen fechas muy tempranas, mientras que otros lo datan en épocas tan tardías como la Rebelión de Bar Kojba.[11] La teoría de la datación temprana recibió un impulso importante cuando el erudito español José O'Callaghan afirmó que el papiro 7Q5, descubierto en Qmram, era un fragmento del evangelio de Marcos. De ser cierta esta hipótesis, el evangelio de Marcos podría ser anterior al año 50. Sin embargo, la mayor parte de los eruditos bíblicos rechaza la hipótesis de O'Callaghan de que el papiro se corresponda con el texto de Marcos.[12] [13] [editar] ContenidoEl evangelio de Marcos relata la historia de Jesús de Nazaret desde su bautismo hasta su resurrección. A diferencia de los otros dos sinópticos, no contiene material narrativo acerca de la vida de Jesús anterior al comienzo de su predicación.Marcos está de acuerdo en lo esencial con la teología paulina: lo único importante en Jesús es su muerte y su resurrección. No obstante, a diferencia de Pablo, se ocupa de consignar los hechos y dichos de Jesús. [editar] Exorcismos y curacionesEn Marcos se relatan cuatro exorcismos practicados por Jesús:

Existen otros ocho relatos detallados de curaciones de diversas dolencias realizadas por Jesús:

J. M. González Ruiz: “Paralelos en las teologías marquiana y paulina”, en Revista Catalana de Teología 14 (1989); pp. 323-332. [editar] El final del Evangelio de MarcosEl final del evangelio de Marcos, a partir de Mc 16, 8, en el que se narran las apariciones de Jesús resucitado a María Magdalena, a dos discípulos que iban de camino y a los once apóstoles, así como la ascensión de Jesús, es casi seguro que se trata de una adición posterior.De hecho, en la nota a pie de página de la Biblia de Jerusalén podemos leer lo siguiente: El final de Marcos vv 9-20, forma parte de las Escrituras inspiradas; es considerado como canónico. Esto no significa necesariamente que haya sido redactado por Marcos. De hecho, se pone en duda su pertenencia a la redacción del segundo evangelio. De hecho, los versículos 9-20 no aparecen en ninguno de los manuscritos conservados más antiguos y se ha comprobado que el estilo es muy diferente al resto del evangelio. Orígenes, en el siglo III, cuando cita los relatos de resurrección, se refiere a los otros tres canónicos, pero no a Marcos. Algunos manuscritos, además, añaden otros finales diferentes del actual. La incógnita es si Marcos quiso que tuviese este final, si tuvo que finalizar bruscamente por alguna razón desconocida o si hubo un final que se perdió. [editar] Fuente originalEl texto arameo que probablemente sirvió de fuente a Marcos parece ser en realidad una recopilación de narraciones en fragmentos diversos, que pudieron llegar a los evangelistas como una colección de textos, o bien ya interconectados en una primera historia evangélica. Algunos autores de la tercera búsqueda del Jesús histórico consideran que puede clasificarse cada una de estas unidades literarias en función de sus coincidencias o divergencias entre los evangelios. De este modo, entre las más antiguas se destacarían las narraciones de la Pasión, y entre las más modernas, las de infancia y los materiales propios de cada evangelista.[editar] Notas

[editar] Véase también[editar] Enlaces externos

Gospel of MarkFrom Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Greek: κατὰ Μᾶρκον εὐαγγέλιον, kata Markon euangelion, or τὸ εὐαγγέλιον κατὰ Μᾶρκον, to euangelion kata Markon), commonly called the Gospel of Mark or simply Mark, is the second book of the New Testament. This Canonical account of the life of Jesus is one of the Synoptic Gospels. It was thought to be an epitome, and accordingly, its place as the second gospel in most Bibles. However, most contemporary scholars now regard it as the earliest of the canonical gospels[1] (c 70).[2]

The Gospel of Mark narrates the ministry of Jesus of Nazareth from his baptism by John the Baptist to the resurrection and it concentrates particularly on the last week of his life (chapters 11–16, the trip to Jerusalem). Its swift narrative portrays Jesus as a heroic man of action,[2] an exorcist, a healer and miracle worker. It calls him the Son of Man,[3] the Son of God,[4] and the Messiah or Christ.[5]

Two important themes of Mark are the Messianic Secret and the obtuseness of the disciples. In Mark, Jesus often is guarded regarding aspects of his identity and certain actions.[6] Jesus uses parables to explain his message and fulfill prophecy (4:10-12). At times, the disciples have trouble understanding the parables, but Jesus explains what they mean, in secret (4:13-20, 4:33-34). The disciples also fail to understand the implication of the miracles that he performs before them.[2]

Christian tradition names Saint Mark, Saint Peter's translator, as the evangelist. Contemporary academics, however, conclude that the author is unknown.

[edit] CompositionThe Gospel of Mark was composed by an anonymous author,[2] traditionally believed to be Mark the Evangelist (also known as John Mark), a disciple of Peter and a cousin of Barnabas.[7] Tradition held that the Gospel of Mark was based on the preaching of a disciple of Peter.[1][8][9][10][11][edit] AuthorshipAs early as Papias in the early 2nd century, this gospel was attributed to Mark,[7] who is said to have recorded the Apostle Peter's discourses. Papias cites his authority as being John the Presbyter. While the text of Papias is no longer extant, it was quoted by Eusebius of Caesarea:

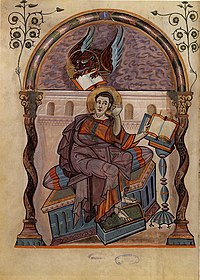

Ehrman, MacDonald and Nineham believe that the Gospel of Mark contains mistakes concerning Galilean geography and customs,[17][18][19] which might suggest that the author was not native to the Holy Land, as was the historical Peter.[20] Other scholars, notably Craig Blomberg, disagree.[21] John McRay has said on the issue "when everything is put into the appropriate context, there is no problem with Mark's account".[22] It has been argued that there is an impending sense of persecution in the gospel, and that this could indicate it being written to sustain the faith of a community under such a threat. As the main Christian persecution at that time was in Rome under Nero, this has been used to place the writing of the Gospel in Rome.[23] Furthermore, it has been argued that the Latinized vocabulary[24] employed in Mark (and in neither Matthew nor Luke) shows that the Gospel was written in Rome. Also cited in support is a passage in First Peter: "The chosen one at Babylon sends you greeting, as does Mark, my son.";[25] Babylon being interpreted as a derogatory or code name for Rome, as the famous ancient city of Babylon ceased to exist in 275 BC. Jerome affirms that Mark the disciple and interpreter of Saint Peter, and the follower and Apostle of Jesus Christ. According to Eusebius,[26] Mark composed a gospel embodying what he had heard Peter preach in Rome.[27][28][29] However, certain scholars dispute the connection of the gospel with persecution, identified with Nero's persecution in Rome, asserting that persecution was widespread, albeit sporadic beyond the borders of the city of Rome.[30] [edit] Possible Primary Source to the Synoptic GospelsSee also: Synoptic Gospels  The first page of Mark in Minuscule 544 However, all the aforementioned scholars accept Marcan Priority and that the Gospel of Mark was a primary source document.[41][42][43][44] Not only does modern critical scholarship support this conclusion,[45] but the writings of Church Fathers do as well. For example, Jerome's Illustrious men, which was a major bibliographical text containing a list of early authors and their writings cites over 800 Christian sources as well as 31 from Josephus, 36 from Phils and 25 lost documents. Mark and his gospel are at the top of Jerome's list in Section 1, exactly where the first written account of the life of Jesus Christ should be located.[46] Mark's gospel is a short, Koine Greek basis for the Synoptic Gospels. It provides the general chronology, from Jesus' baptism to the empty tomb.[45] The majority of scholars still believe that the Gospel of Mark was combined with Q, Q being the second primary source to form the Synoptic gospels. However the issue of Q is far from settled. Even some supporters of the Q source hypothesis have concerns. If Q did exist, these sayings of Jesus would have been highly treasured in the Early Church. It remains a mystery how such an important document, which was the basis of the two canonical Gospels, could be totally lost. An even greater mystery why the extensive Church Catalogs compiled by Eusebius and Nicephorus would omit such an important work, yet include such spurious accounts as the Gospel of Peter and the Gospel of Thomas. The existence of a highly treasured dominical sayings document in circulation going totally unmentioned by the Fathers of the Early Church, remains one of the great conundrums of Modern Biblical Scholarship.[47][48] James Edwards looked at the first section of Illustrious Men and found the Gospel of Mark where it should be, as it was the first gospel written and was the basis of later gospels. Following it should be Q. But not only is Q not where it should be at the top of Jerome's list, this treasured work recording the Logia of Christ is mentioned nowhere by Jerome. Rather, the first seminal document is not Q but the Gospel of the Hebrews. Section 2 on James, the largest in the Illustrious Men, is mainly about this Hebrew Gospel (one-third of the section). The entirety of the third section is devoted to the Hebrew Gospel as well. In "the place of honor" that should be given "the phantom Q" we find a Hebrew usurper.[49] From this basis James Edwards expands the Parker Hypothesis into the Hebrew Gospel Hypothesis. In meticulous detail he puts forward his solution to the synoptic problem. This Hypothesis states Matthew wrote a small Hebrew Gospel called the Gospel of the Hebrews and this primary source along with Mark formed the basis for the Gospel of Luke and possibly Matthew .[50] [edit] AudienceThe general theory is that Mark wrote a Hellenistic gospel, primarily for an audience of gentile Greek-speaking residents of the Roman Empire. Jewish traditions are explained, clearly for the benefit of non-Jews (e.g., Mark 7:1–4; 14:12; 15:42). Aramaic words and phrases are also expanded upon by the author, e.g., ταλιθα κουμ (talitha koum, Mark 5:41); κορβαν (Corban, Mark 7:11); αββα (abba, Mark 14:36).Alongside these Hellenistic influences, Mark makes use of the Old Testament in the form in which it had been translated into Greek, the Septuagint, for instance, Mark 1:2; 2:23–28; 10:48b; 12:18–27; also compare 2:10 with Daniel 7:13–14. Those who seek to show the non-Hellenistic side of Mark note passages such as 1:44; 5:7 ("Son of the Most High God"; cf. Genesis 14:18–20); Mark 7:27; and Mark 8:27–30. These also indicate that the audience of Mark has kept at least some of its Jewish heritage, and also that the gospel might not be as Hellenistic as it first seems. The Gospel of Mark contains several literary genres and came at a time when Christian faith was rising. Professor Dennis R MacDonald writes:

[edit] Losses and early editingMark is the shortest of the canonical gospels. Manuscripts, both scrolls and codices, tend to lose text at the beginning and the end, not unlike a coverless paperback in a backpack.[52] These losses are characteristically unconnected with excisions. For instance, Mark 1:1 has been found in two different forms. Most manuscripts of Mark, including the 4th-century Codex Vaticanus, have the text "son of God",[53] but three important manuscripts do not. Those three are: Codex Sinaiticus (01, א; dated 4th century), Codex Koridethi (038, Θ; 9th century), and the text called Minuscule 28 (11th century).[54] Bruce Metzger's Textual Commentary on the Greek New Testament states: "Since the combination of B D W all in support of [Son of God] is extremely strong, it was not thought advisable to omit the words altogether, yet because of the antiquity of the shorter reading and the possibility of scribal expansion, it was decided to enclose the words within square brackets."Interpolations may not be editorial, either. It is a common experience that glosses written in the margins of manuscripts get incorporated into the text as copies are made. Any particular example is open to dispute, of course, but one may take note of Mark 7:16, "Let anyone with ears to hear, listen," which is not found in early manuscripts. Revision and editorial error may also contribute. Most differences are trivial but Mark 1:41, where the leper approached Jesus begging to be healed, is significant. Early (Western) manuscripts say that Jesus became angry with the leper while later (Byzantine) versions indicate that Jesus showed compassion. This is possibly a confusion between the Aramaic words ethraham (he had pity) and ethra'em (he was enraged).[55] Modern translations follow the later manuscripts for this passage.[56] [edit] EndingMain article: Mark 16 Starting in the 19th century, textual critics have commonly asserted that Mark 16:9–20, describing some disciples' encounters with the resurrected Jesus, was a later addition to the gospel. Mark 16:8 stops at the empty tomb without further explanation. The last twelve verses are missing from the oldest manuscripts of Mark's Gospel.[57] The style of these verses differs from the rest of Mark, suggesting they were a later addition. In a handful of manuscripts, a "short ending" is included after 16:8, but before the "long ending", and exists by itself in one of the earliest Old Latin codices, Codex Bobiensis. By the 5th century, at least four different endings have been attested. (See Mark 16 for a more comprehensive treatment of this topic.) Possibly, the Long Ending (16:9-20) started as a summary of evidence for Jesus' resurrection and the apostles' divine mission, based on other gospels.[58] It was likely composed early in the second century and incorporated into the gospel around the middle of the second century.[58]Therefore, the Gospel of Mark may have originally ended abruptly at Mark 16:8. This has become problematic for scholars, as it is unlikely that a Christian author would have intentionally ended his gospel in such a fashion. The most common explanation is that the ending was lost. This is not uncommon with ancient scrolls due to their wearing patterns. The gospel may have been be unfinished, due to death or some form of persecution. Finally Mark could have been a two volume work in the tradition of Luke-Acts, the second volume being lost or unfinished.[52][59][60] [61] Irenaeus, c. 180, quoted from the long ending, specifically as part of Mark's gospel.[62] The 3rd-century theologian Origen of Alexandria quoted the resurrection stories in Matthew, Luke, and John but failed to quote anything after Mark 16:8, suggesting that his copy of Mark stopped there. Eusebius and Jerome both mention the majority of texts available to them omitted the longer ending.[63] Critics are divided over whether the original ending at 16:8 was intentional, whether it resulted from accidental loss, or even the author's death.[64] Those who believe that 16:8 was not the intended ending argue that it would be very unusual syntax for the text to end with the conjunction gar (γάρ), as does Mark 16:8, and that thematically it would be strange for a book of good news to end with a note of fear (ἐφοβοῦντο γὰρ, "for they were afraid").[65] If the 16:8 ending was intentional, it could indicate a connection to the theme of the "Messianic Secret". This abrupt ending is also used to support the identification of this book as an example of closet drama, which characteristically ended without resolution and often with a tragic or shocking event that prevents closure.[66] [edit] Characteristics Minuscule 2427 – "Archaic Mark" [edit] TheologyChristians consider the Gospel of Mark to be divinely inspired and will see the gospel's theology as consistent with that of the rest of the Bible. Each sees Mark as contributing a valuable voice to a wider Christian theology, though Christians sometimes disagree about the nature of this theology. However, Mark's contribution to a New Testament theology can be identified as unique in and of itself.Mark is seen as an historian/theologian and declares that his account is "The Gospel of Jesus Christ". The "Suffering Messiah" is central to Mark's portrayal of Jesus, his theology and the structure of the gospel. This knowledge is hidden and only those with spiritual insight may see. The concept of hidden knowledge may have become the basis of the Gnostic Gospels.[68] John Killinger, arguing that, in Mark, the resurrection account is hidden throughout the gospel rather than at the end, speculates that the Markan author might himself have been a Gnostic Christian.[69] [edit] AdoptionismChristians believe that Jesus was the Son of God. The majority Christian view is that He was conceived by the Holy Spirit and was born of the Virgin Mary.However, there is a minority Christian belief called Adoptionism. Adoptionists believe that Jesus was fully human, born of a sexual union between Joseph and Mary.[70][71] Jesus only became divine, i.e. (adopted as God's son), later at his baptism.[72] He was chosen as the firstborn of all creation because of his sinless devotion to the will of God.[73][74] Adoptionism probably arose among early Jewish Christians seeking to reconcile the claims that Jesus was the Son of God with the strict monotheism of Judaism, in which the concept of a trinity of divine persons in one Godhead was unacceptable. In fact, Bart D. Ehrman argues that adoptionist theology may date back almost to the time of Jesus and his view is shared by many other scholars.[75] The early Jewish-Christian Gospels make no mention of a supernatural birth. Rather, they state that Jesus was begotten at his baptism. The theology of Adoptionism fell into disfavor as Christianity left its Jewish roots and Gentile Christianity became dominant. Adoptionism was declared heresy at the end of the second century, and was rejected by the Emperor Constantine at the First Council of Nicaea, which wrote the orthodox doctrine of the Trinity and identifies Jesus as eternally begotten of God. The Creed of Nicaea now holds Jesus was born of the Holy Spirit and the Virgin Mary. (See Virgin Birth).[76] Adoptionism may go back as far as St. Matthew and the Apostles.[75] According to the Church Fathers,[77] the first gospel was written by the Apostle Matthew, and his account was called the Gospel of the Hebrews or the Gospel of the Apostles.[78][79] [80] [81][82] This, the first written account of the life of Jesus was adoptionist in nature. The Gospel of the Hebrews has no mention of the Virgin Birth and when Jesus is baptized it states, "Jesus came up from the water, Heaven was opened, and He saw the Holy Spirit descend in the form of a dove and enter into Him. And a voice from Heaven said, ‘You are my beloved Son; with You I am well pleased.’ And again, ‘Today I have begotten You.’ Immediately a great light shone around the place".[83][84][85] Scholars also see Adoptionist theology in the Gospel of Mark. Mark has Jesus as the Son of God, occurring at the strategic points of 1:1 ("The beginning of the gospel about Jesus Christ, the Son of God") and 15:39 ("Surely this man was the Son of God!"), but the Virgin Birth of Jesus has not been developed.The phrase "Son of God" is not present in some early manuscripts at 1:1. Bart D. Ehrman uses this omission to support the notion that the title "Son of God" is not used of Jesus until his baptism, and that Mark reflects an adoptionist view.[86] However, the authenticity of the omission of "Son of God" and its theological significance has been rejected by Bruce Metzger and Ben Witherington III.[87][88] By the time the Gospels of Luke and Matthew were written, Jesus is portrayed as being the Son of God from the time of birth, and finally the Gospel of John portrays the Son as existing "in the beginning".[86] [edit] Meaning of Jesus' deathThe only explicit mention of the meaning of Jesus' death in Mark occurs in 10:45 where Jesus says that the "Son of Man came not to be served but to serve, and to give his life as a ransom (lutron) for many (anti pollōn)." According to Barnabas Lindars, this refers to Isaiah's fourth servant song, with lutron referring to the "offering for sin" (Isaiah 53:10) and anti pollōn to the Servant "bearing the sin of many" in Isaiah 52:12.[89] The Greek word anti means "in the place of", which indicates a substitutionary death.[90]The author of this gospel also speaks of Jesus' death through the metaphors of the departing bridegroom in 2:20, and of the rejected heir in 12:6-8. He views it as fulfilling Old Testament prophecy (9:12, 12:10-11, 14:21 and 14:27). Many scholars believe that Mark structured his gospel in order to emphasise Jesus' death. For example, Alan Culpepper sees Mark 15:1-39 as developing in three acts, each containing an event and a response.[91] The first event is Jesus' trial, followed by the soldiers' mocking response; the second event is Jesus' crucifixion, followed by the spectators mocking him; the third and final event in this sequence is Jesus' death, followed by the veil being rent and the centurion confessing, "truly this man was the Son of God." In weaving these things into a triadic structure, Mark is thereby emphasising the importance of this confession, which provides a dramatic contrast to the two scenes of mocking which precede it. D. R. Bauer suggests that "by bringing his gospel to a climax with this christological confession at the cross, Mark indicates that Jesus is first and foremost Son of God, and that Jesus is Son of God as one who suffers and dies in obedience to God."[92] Joel Marcus notes that the other Evangelists "attenuate" Mark's emphasis on Jesus' suffering and death, and sees Mark as more strongly influenced than they are by Paul's "theology of the cross".[93] [edit] Characteristics of Mark's contentThe narrative can be divided into three sections: the Galilean ministry, including the surrounding regions of Phoenicia, Decapolis, and Cæsarea Philippi (1-9); the Journey to Jerusalem (10); and the Events in Jerusalem (11-16).

[edit] Characteristics of Mark's languageThe phrase "and immediately" occurs nearly forty times in Mark; while in Luke, which is much longer, it is used only seven times, and in John only four times.[96] The word Greek: νομος law ([6]) is never used, while it appears 8 times in Matthew, 9 times in Luke, 15 times in John, 19 times in Acts, many times in Romans.Latin loanwords are often used: speculator, sextarius, centurion, legion, quadrans, praetorium, caesar, census, flagello, modius, denarius.[97] Mark has only a few direct Old Testament quotations: 1:2-3, 4:12, 7:6-7, 11:9-10, 12:29-31, 13:24-26, 14:27. Mark makes frequent use of the narrative present; Luke changes about 150 of these verbs to past tense.[98] Mark frequently links sentences with Greek: και (and); Matthew and Luke replace most of these with subordinate clauses. [edit] Other characteristics unique to Mark

[edit] Secret Gospel of MarkMain article: Secret Gospel of Mark The Secret Gospel of Mark refers to a version of the Gospel of Mark being circulated in 2nd century Alexandria, which was kept from the Christian community at large. This non-canonical gospel fragment was discovered in 1958, by biblical researcher Morton Smith at the Mar Saba monastery.[103]In this fragment, Clement of Alexandria explains that Mark, during Peter's stay in Rome wrote an account of the life of Jesus. Mark selected those events that would be the most helpful to the Church. When Peter died a martyr, Mark left Rome and went to Alexandria. He brought both his own writings and those of Peter. It was here that Mark composed a second more spiritual Gospel and when he died, he left his composition to the Church.[104] The Carpocrates got a copy of this Gospel and they misinterpreted it, which caused problems for the early Church. Some modern scholars maintain it was a clumsy forgery, while others accept this text as being authentic.[105] [106] The nature of the Secret Gospel of Mark as well as Morton Smith's role in its discovery are still being debated.[107][108][109][110] [edit] Canonical StatusA related issue is the adoption of the Gospel of Mark as a Canonical Gospel, given that, like the hypothetical Q, it is largely reproduced in Matthew and Luke, but, unlike Q, it did not become "lost". Traditionally Mark's authority and survival has derived from its Petrine origins (see above "Authorship"). Another possibility has been a supposed Roman origin and an established status there before the other gospels reached Rome.[111] A recent suggestion is that Mark gained widespread popularity in oral performance, apart from readings from manuscript copies. Its widespread oral popularity ensured it a place in the written canon.[112][edit] Content[edit] See also

[edit] Notes

[edit] References

[edit] External links

Disculpen las Molestias

Sri Garga-Samhita | Oraciones Selectas al Señor Supremo | Devotees Vaishnavas | Dandavat pranams - All glories to Srila Prabhupada | Hari Katha | Santos Católicos | JUDAISMO | Buddhism | El Mundo del ANTIGUO EGIPTO II | El Antiguo Egipto I | Archivo Cervantes | Sivananda Yoga | Neale Donald Walsch | SWAMIS jueves 11 de marzo de 2010ENCICLOPEDIA - INDICE | DEVOTOS FACEBOOK | EGIPTO - USUARIOS de FLICKR y PICASAWEBOtros Apartados

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Archivo del blog

-

▼

2010

(40)

-

▼

octubre

(40)

- Categoría:Manuscritos de Nag Hammadi

- Discurso sobre la Ogdóada y la Eneada

- Evangelio de Tomás - Gospel of Thomas

- Nuevo Testamento - New Testament

- Evangelio de Juan - Gospel of John

- Evangelio de Lucas - Gospel of Luke

- Evangelio de Mateo - Gospel of Matthew

- Evangelio de Marcos - Gospel of Mark

- Tratado de la Resurrección

- Tratado Tripartito - Tripartite Tractate

- Apócrifos - Biblical apocrypha

- Gnosticismo - Gnosticism

- Evangelio de Valentín - Gospel of Truth

- Apócrifo de Santiago - Apocryphon of James

- Oración de Pablo - Prayer of the Apostle Paul

- Manuscritos de Nag Hammadi

- Evangelio apócrifo

- Diccionarios de la Biblia - Xabier Pikaza

- tablas

- Tablas de Arqueología - Antipatris - Arqueología

- Ivory and gold in the Delta: excavations at Tell e...

- Indice de Nombres Propios y Temas III - DICCIONARI...

- Indice de Nombres Propios y Temas II - DICCIONARIO...

- URA - ZOAN - DICCIONARIO BIBLICO ARQUEOLOGICO

- TELL ARAQ EL MENSHIYEH - UMMA - DICCIONARIO BIBLIC...

- SINAI - TELL ARPACHIYA - DICCIONARIO BIBLICO ARQU...

- ROSETA, PIEDRA - SINAGOGA - DICCIONARIO BIBLICO A...

- PALERMO, LA PIEDRA DE - ROMA - DICCIONARIO BIBLICO...

- MOAB, MOABITAS - PALEONTOLOGÍA - DICCIONARIO BIBLI...

- LIBRO DE LOS MUERTOS, EL - MIZPA - DICCIONARIO BIB...

- JERICO (NUEVO TESTAMENTO) - LEY, MESOPOTAMICA - DI...

- HABACUC, COMENTARIO DE - JERICO (ANTIGUO TESTAMENT...

- FERTIL MEDIA LUNA - GUERRA - DICCIONARIO BIBLICO ...

- EFESO - FENICIA, FENICIOS - DICCIONARIO BIBLICO A...

- CASITAS - EDOM, EDOMITAS - DICCIONARIO BIBLICO AR...

- BABILONIA, LAS CRONICAS DE - CARRHAE - DICCIONARIO...

- ARQUITECTURA - BABILONIA - DICCIONARIO BIBLICO AR...

- ANTIPATRIS, AFEC - ARQUEOLOGÍA - DICCIONARIO BIBLI...

- ABGAR - ANTIOQUIA (DE SIRIA) - DICCIONARIO BIBLICO...

- LEYENDA DE ADAPA

-

▼

octubre

(40)

Datos personales

lunes, 25 de octubre de 2010

Evangelio de Marcos - Gospel of Mark

Suscribirse a:

Enviar comentarios (Atom)

No hay comentarios:

Publicar un comentario